In this regular monthly feature, Dr. Darria and CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta cover the top health news of the month.

This month topics include Zika virus and concussion news.

A Second Opinion with Dr. Sanjay Gupta

Dr. Darria and CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta cover the top health news of the month.

Additional Info

- Segment Number: 3

- Audio File: sharecare/1607sc2c.mp3

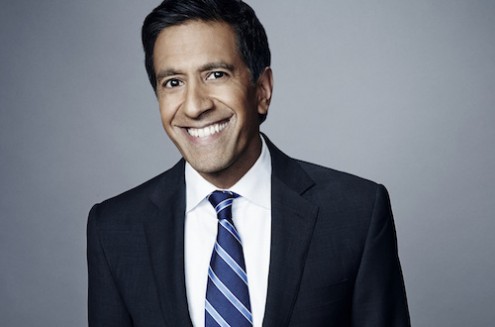

- Featured Speaker: Sanjay Gupta, MD

- Guest Website: CNN Profiles: Dr. Sanjay Gupta

- Guest Twitter Account: @drsanjaygupta

-

Guest Bio:

Dr. Sanjay Gupta is the multiple Emmy® award winning chief medical correspondent for CNN. Gupta, a practicing neurosurgeon, plays an integral role in CNN's reporting on health and medical news for all of CNN's shows domestically and internationally, and contributes to CNN.com. His medical training and public health policy experience distinguishes his reporting from war zones and natural disasters, as well as on a range of medical and scientific topics, including the recent Ebola outbreak, brain injury, disaster recovery, health care reform, fitness, military medicine, and HIV/AIDS. Additionally, Dr. Gupta is the host of Vital Signs for CNN International and Accent Health for Turner Private Networks.

Dr. Sanjay Gupta is the multiple Emmy® award winning chief medical correspondent for CNN. Gupta, a practicing neurosurgeon, plays an integral role in CNN's reporting on health and medical news for all of CNN's shows domestically and internationally, and contributes to CNN.com. His medical training and public health policy experience distinguishes his reporting from war zones and natural disasters, as well as on a range of medical and scientific topics, including the recent Ebola outbreak, brain injury, disaster recovery, health care reform, fitness, military medicine, and HIV/AIDS. Additionally, Dr. Gupta is the host of Vital Signs for CNN International and Accent Health for Turner Private Networks.

-

Transcription:

Sharecare. Helping you find experts. The top minds in healthy medicine. It’s Sharecare Radio with Dr. Darria Long Gillespie on RadioMD.com.

DR. DARRIA: Welcome back. It’s Dr. Darria. We hear a lot of health news every month. Sometimes it can seem confusing and overwhelming. So, we have our monthly segment today called our Second Opinion in which I talk with Dr. Sanjay Gupta and we’ll cut through the confusion of that information to share what you really need to know. He really needs no introduction. Dr. Sanjay Gupta is author of New York Times best-selling books Chasing Life and Cheating Death and, of course, he’s CNN’s Chief Medical Correspondent. He is a practicing neurosurgeon and, in his free time, he is a wonderful dad to three daughters. Sanjay, thank you so much for joining us.

DR. GUPTA: Thank you, Darria. Thanks for having me.

DR. DARRIA: I am so glad you are here because I know our very first topic is something that I want to dive into. It’s something that is really concerning to me – it’s the Zika virus. It’s been all over the news but there are still some things I want to know and I know our listeners want to know. Number one, it’s not a new virus but what is going on? Why is it suddenly so prevalent?

DR. GUPTA: It’s kind of a really fascinating story. You’re right. It’s not a new virus. It’s been around, really, since the late 40’s. It was identified in the primates in the Zika Forrest of Uganda. That’s where it got its name. Then, it was, I think, in the 50’s before they found that it was actually in human beings. So, it’s been around for some time. It started to spread, I think, in part because of the globalized world in which we live. Most likely, what happened is somebody who had the Zika virus in their system, but probably wasn’t sick, got on a plane, traveled to a place where the type of mosquitos that can spread Zika virus lived and were spreading and that person got bit by a mosquito. That same mosquito subsequently bit somebody else and that started the transmission. We know the little island of Yap, probably an island most people have never heard of. You can find it on a map.

DR. DARRIA: Did you make that up?

DR. GUPTA: No, it’s a real island in Micronesia. But that little island had 73% of the population infected. I guess that’s what it means to go viral. Right?

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: That’s what happened. Then, from there, it just sort of started hopscotching and zigzagging around the world. But, there is another reason, Dr. Darria, which you will appreciate and your listeners may already know. When we’ve never seen a virus before – when our population of people has never been exposed to a virus before--we don’t have any natural immunity to it. Our body doesn’t try and fight it. When a virus shows up all the sudden that we’ve never seen before, it can spread much more quickly because it gets into our bodies and replicates itself. That makes it easier for mosquitos to bite us, take some of that virus into their body and then subsequently give it to somebody else.

DR. DARRIA: I was going to ask, on that island of Yap, do they have this issue of microcephaly or is it that they have this immunity before they ever become pregnant?

DR. GUPTA: It’s a great question. With microcephaly--we tried to look into this, but you’re looking into a very small population of people. Yes, they have had cases of microcephaly but they had cases of microcephaly even before Zika virus was known to be there. If the cases went up from, let’s say 12 cases in a given year, to 20 cases in a given year, is that enough to say, “Well, this is definitely due to Zika?” When you deal with small numbers like on some of these very small islands, it’s hard to really draw a cause and effect. As you know, no scientist that is looking into this can say for certain that Zika virus causes microcephaly. There are strong, strong suspicions and strong suggestions but it takes a lot of time and a lot of numbers and a lot of people to really make that connection clear.

DR. DARRIA: Exactly. You’re right. I want to take a moment because I don’t think a lot of people understand microcephaly exactly. It is a term that we are hearing in the news. Talk about what it means and what are the consequences of it.

DR. GUPTA: First of all, “micro”, as people know, just means small and “cephaly” – cephalic is the head. Strictly defined, it means “small head”. But, what we’re talking about here is babies’ heads and their brains not developing properly during the time that they are developing. As a result, when we say that the brain has not developed properly, it means that certain cells in the brain didn’t move to areas where they should have and, as a result, the brain didn’t grow to its normal size. The skull didn’t grow to its normal size. So, what you see is a baby with a very small head but what you know is that it is not just a small head, it’s a small brain and a brain that is not developed properly.

DR. DARRIA: Right. We’re not just talking little, cute heads. It’s really a devastating, incomplete development.

DR. GUPTA: You’re absolutely right. People who read about this will say, “Well, there’s a whole wide range of microcephaly.” It can be, in certain people, more of a cosmetic sort of thing but it really depends on why microcephaly developed. In this case, if it’s the virus that is causing the problem in the brain and the central nervous system such that the brain and head are small, they haven’t developed properly. That can potentially even be a lethal problem. We know over 50 babies have died because of this.

DR. DARRIA: That’s so terrifying. The question that everybody wants to know: if a woman is considering getting pregnant or is pregnant, where does she need to stay away from right now and for the next three of four months?

DR. GUPTA: These are two different groups of people – women who are currently pregnant and women who are thinking about getting pregnant. Here’s what I would say and, you know what? I get this question all the time. My friends have been emailing me. I have lots of friends who live in South America. If you are pregnant – and for this conversation I’ll say at any stage in your pregnancy, although earlier stages of pregnancy seem to be a little bit more at risk – but any stage of your pregnancy, if you don’t need to be in an area where Zika virus is spreading, don’t be in that area. All those countries have been listed and identified. I think there are 24 or 25 countries now that are on that list. For women who think, “Well look, I’m not pregnant and, by the way, I’m sure that I’m not pregnant” – a lot of people say, “I’m not pregnant.” You need to be sure.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: You’ve got a trip coming up and you think, “Oh, I’m not pregnant.” Be sure.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: Take a pregnancy test.

DR. DARRIA: I see this in the E.R. all the time. I have told many a surprised female that she is pregnant who did not know. So, yes.

DR. GUPTA: “Who me? How did that happen?” Anyway, be sure you’re not pregnant and if you are not pregnant and, let’s say you get a Zika infection and then a month later from now, you’re thinking about having a baby--or two months or three months, whatever it may be--you should be fine. The Zika virus appears to clear the system, clear the blood, within about seven days, on average. It could be a little longer or a little shorter in some people. But, after that, your future pregnancies should not be at risk.

DR. DARRIA: Okay. So, potentially, if you do go to one of those places and you’re not pregnant, even if you say I’m going to wait a couple of weeks or a month or so, then you should be fine because with Zika, you don’t always know that you’ve caught it either, right? Because in some people it can be a really mild symptom.

DR. GUPTA: In most people, Dr. Daria, it will be either mild or no symptoms which is something that I want to make sure doesn’t get lost in all of this because I think people are frightened about this and we want to make sure that we’re not trying to inspire fear at all. Eighty percent of people, roughly, who get this will have mild or no symptoms. You wouldn’t even know to get checked. You wouldn’t even know. The better sense of valor and caution here is that if you’re thinking about getting pregnant, just wait. “Maybe I could have the infection. I don’t know. But, I do know that if I did have the infection, I got back from this are on such and such date. By 7 days after that, by 14 days after that for sure, the virus should be clear. I am no longer at risk when it comes to pregnancy.”

DR. DARRIA: Okay. That’s great to know. Now, you mentioned earlier when you first started talking, you said the earlier stages are at higher risk. That was one thing I was going to ask you. Is one trimester more at risk than the others?

DR. GUPTA: The absolute right answer, I think, is that we don’t know for sure. I think what you’re hearing from some of the scientists who are looking at the children who have microcephaly that earlier stages of pregnancy--earlier trimester--are probably riskier than later trimesters. Again, until you have enough data to really say for sure, you can’t say for sure.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: What I will tell you is that the guidance from the CDC is…Let’s say me, for example. I’m probably going to go to South America to do some reporting on this. If I came back from there, even if I wasn’t sick, and my wife was currently pregnant--she’s not, but if she was currently pregnant – the advice is that I either abstain or practice absolutely safe sex for the duration of the pregnancy, for the entire pregnancy because we simply don’t know for sure still what is the riskiest stage. But, again, earlier stages are probably slightly riskier than later stages.

DR. DARRIA: You’re getting to the fact that we have seen people with transmission through intercourse as well not just through the mosquitos.

DR. GUPTA: That’s right. I should have mentioned that because that is a little bit of an unusual characteristic of this virus. You and I have both studied malaria. Malaria is something that can be transmitted by mosquitos but not by sex. It’s not a virus, but it’s a type of pathogen. HIV can be transmitted by sex, but not by mosquitos. This particular virus – Zika virus--appears to be able to be transmitted in both ways – by mosquitos primarily, but also by sex. What is really interesting and this may be more than you want to know, but I think it is so fascinating. That is that there are certain areas of the body that are what are called “immune privileged”. That means our immune system kind of leaves those areas alone. One of the areas in men is the testacles where semen is produced. Probably the reason it is left alone is because you don’t want your immune system attacking your future progeny building blocks.

DR. DARRIA: Right.

DR. GUPTA: It would make it hard for men to have children.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: But, it also means that viruses can hang out there. They can more easily evade the immune system there and they can become sexually transmitted, as a result.

DR. DARRIA: That’s fascinating.

DR. GUPTA: This particular virus – Zika virus--does appear to be sexually transmissible.

DR. DARRIA: Okay.

DR. GUPTA: Probably not nearly in the same numbers as mosquitos, but it is possible.

DR. DARRIA: To that point, you said if a woman is not pregnant and she comes back from one of these countries, she needs to wait 7, 14 days, maybe up to a month to know that the virus has cleared out of her system. But, it sounds like it could stay in the male system longer. So, how long does he need to wait?

DR. GUPTA: Right now, the guidance from the CDC has been at least 28 days. That is a little bit of an arbitrary number. We knew, for example, with Ebola, that the virus could stay in semen for, I think, a few months even afterwards. There are probably going to be clearer numbers on that, again, as this is tested and examined more and more. Right now, the big concern is still, though, that once the woman is already pregnant, getting an infection at that point seems to be the biggest concern.

DR. DARRIA: Got it. The thought being that if she’s not already pregnant, that it is less of an issue.

DR. GUPTA: Correct.

DR. DARRIA: Got it. Okay. But it sounds like this is something that we’re saying women--if they are considering getting pregnant; men who are spouses or partners of women who are considering getting pregnant need to be careful as well is the bottom line.

DR. GUPTA: Yes. You know what’s fascinating, Dr. Darria? This is real time that we’re learning this. You and I have studied all kinds of different diseases over our medical careers. This is one that we probably didn’t study.

DR. DARRIA: No.

DR. GUPTA: There was no reason to.

DR. DARRIA: It was not in the medical books.

DR. GUPTA: Most people didn’t know about Ebola up until the last 18 months and, now, we’re learning about Zika. And you know what? We’ll be learning about another pathogen soon as well. That’s not to scare people but, again, it’s the world in which we live. Pathogens that were typically just living in a very small area of the world can now travel all over. So, an infectious disease anywhere in the world now is an infectious disease everywhere in the world.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: It doesn’t mean that they are necessarily deadly but it is something that we have to be mindful of.

DR. DARRIA: It is and especially as they get transmitted to a different part of the world, as you mentioned, you’re faced with a virus to which your body doesn’t have immunities. So, it may have different outcomes as well.

DR. GUPTA: Exactly.

DR. DARRIA: One last question on this getting transferred to a different part of the world. We talked earlier about the Aedes mosquito, in the summer, can come up the East coast. You were saying that it may not actually carry the Zika virus up the East coast. What do we need to know about it coming into May, June and July?

DR. GUPTA: What I would tell you is, the mosquito that we’re talking about is the female Aedes aegypti mosquito. It’s a mosquito that tends to be a daytime biter. So, these are mosquitos that are biting you during the day time as opposed to the malaria mosquito, for example, which bites at night. There are other infectious diseases that this particular mosquito has carried – dengue fever is an example of that, chikungunya is an example of that.

DR. DARRIA: Which we were hearing a lot about a year ago, or so.

DR. GUPTA: That’s right. So, we have these same mosquitos in the United States, primarily in the southern states, but despite the fact that dengue has tens of millions of cases of dengue fever around the world every year, you still only see really limited outbreaks in the United States. It’s not just the mosquitos that are necessary for this to start spreading, it’s also the conditions. This may sound very simple, but screens on windows, air conditioned buildings, not having standing water, like you might see in a very urbanized area makes a huge difference. Where you see this spreading a lot, for example, in places like in Brazil, it’s typically areas that don’t have some of those amenities that we take very much for granted. The mosquitos are here. The mosquitos that transmit Zika are here and they have been here for a long time. But, that’s just one of the ingredients necessary for this to start spreading. My prediction is that we will see more cases of Zika in the United States. The majority of them will be from people who have traveled to one of these countries. We will see some localized outbreaks of Zika like we have of dengue but I don’t think we’re going to see the numbers like they’ve seen in South America.

DR. DARRIA: Do women who are considering being pregnant or who are in the early stages of pregnancy right now, so they’ll be pregnant this summer, do they need to do anything extra if they are in the Southeastern portions of the U.S.?

DR. GUPTA: That’s a great question. I live in the Southeastern part of the U.S.

DR. DARRIA: We’re here in Atlanta. Exactly.

DR. GUPTA: I would say that it is going to be the same guidance that women are getting anywhere else with mosquitos. You just want to do all you can to prevent mosquito bites. Obviously, I know that is not practical and the mosquitos sometimes are really hard to avoid. But, again, the idea of it starting to spread, which is really the big concern if it starts to spread in this area. That would be the biggest concern for women who are pregnant. I think that is very unlikely in a place like Atlanta. In certain places in south Florida and south Texas, for example, it’s going to be more likely. I think some of the precautions that are going to need to be taken there are going to be stricter than in years past. Eliminating all sources of standing water, using insecticides in certain areas to prevent mosquitos and really limiting the amount of time that women are potentially exposed to mosquitos. I don’t think the idea of mandatory delay of pregnancy like they’ve talked about in El Salvador, for example, is practical or something that would work in the United States.

DR. DARRIA: Okay. Good to know and, hopefully, it may not be necessary. You mentioned some of the insecticides. Number one, if a women is pregnant, what do you recommend that she use for mosquito repellant because she doesn’t want to have secondary problems with that?

DR. GUPTA: I have asked folks at the CDC about that very question. I said, “I hope we’re not giving mixed message here.” On one hand, we’re saying if you’re a pregnant woman, you need to be more concerned about Zika virus. On the other hand, we’re telling you to use lots and lots of bug spray.

DR. DARRIA: Yes.

DR. GUPTA: Is that okay for you, mom, and for baby as well? The answer that I’ve gotten, and we’ve talked to several people, is that the type of insect repellants that you buy with DEET are fine. You don’t absorb enough of it across the skin to be a problem, either for mother or for babies. I think use those insect sprays, make sure you’re not being sparing with them because you’re concerned about impact on baby. They seem to be safe.

DR. DARRIA: You can use clothing. You can use long-sleeved clothing and things that are going to minimize the chances that you are actually going to be bitten in the first place as well--or attract insects.

DR. GUPTA: Absolutely. There are all sorts of different strategies for that now, like long-sleeve clothing. Some of this is not going to feel like it is earth shattering information. People do the best they can to avoid mosquitos.

DR. DARRIA: On the last question, you mentioned doing harm by the insecticide that we are trying to use to target the mosquitos. There have been some conversations that it was a larvaecide itself that may have had an impact and been a catalyst for these microcephaly cases. What’s the truth on that?

DR. GUPTA: Let me tell you two things. First of all, all that you’re hearing about Zika virus and microcephaly, the absolute cause and effect has not been established. We can’t say absolutely, 100% that the Zika virus causes microcephaly but, look, the suspicion is really, really strong. It could take a long time to develop those cause and effect relationships. What has happened more recently is that a group of doctors in Argentina, basically, have said that the larvaecide known as Pyriproxyfen could be behind the microcephaly. So, they’re saying it’s not the Zika virus; it’s the insecticide that’s actually causing the problem. We looked into this. First of all, the World Health Organization has looked into this and said that there is no evidence of that. We know that in areas where they don’t use this larvaecide, there has still been an increase in microcephaly cases and there is really no evidence that this insecticide is causing these problems. But, look, we’ve seen it over and over again. When there is a vacuum of information, sometimes bad information will fill that vacuum. Right now, use the insecticides. It’s one of your best bets.

DR. DARRIA: Alright. Dr. Sanjay Gupta, thank you so much. Thanks for clearing that up for us. We will all try to keep safer. For all of our listeners, you can follow Dr. Gupta on Facebook at Facebook.com/DrSanjaGupta; Twitter @DrSanjaGupta or order his books Chasing Life, Cheating Death and Monday Morning on Amazon. Don’t forget Tweet us @SharecareInc or me @DrDarria. Thanks for listening to Sharecare Radio on RadioMD. We’ll talk to you next week and stay well.

[END OF RECORDING]

- Length (mins): 10

- Waiver Received: No

- Host: Darria Long Gillespie, MD, MBA

Published in

Sharecare Radio

Tagged under