Inactive (722)

Children categories

University of Virginia Health System (175)

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1JkoiKFuCQmWJsu92gIyaRHywp6JgkKouIV5tbKYQk2Y/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=pdf

View items...Saint Peter’s Better Health Update (10)

Saint Peters Health System

Saint Peter’s Better Health Update

Florida Hospital - Health Chat (19)

$current_analytic_report = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1JkoiKFuCQmWJsu92gIyaRHywp6JgkKouIV5tbKYQk2Y/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=pdf";

View items...Additional Info

- Segment Number 4

- Audio File st_peter/1430sp2d.mp3

- Doctors Siegel, Scott

- Featured Speaker Scott Siegel, MD

-

Guest Bio

Scott Siegel, MD. is the Director, Pediatric Anesthesiology The Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital

For more information about Saint Peter’s Healthcare System -

Transcription

Bill Klaproth (Host): Children require special care whenever they undergo a surgery and that is where the pediatric anesthesiologist comes in. Here to explain more is Dr. Scott Siegel, a pediatric anesthesiologist at the Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital. Dr. Siegel, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today. How are pediatric anesthesiologists especially trained to care for children?

Dr. Scott Siegel (Guest): Okay. It’s a good place to start, Bill. People understand anesthesiologists are physicians. After medical school, anesthesiologists do a residency in anesthesia, usually two to three years. And then, the pediatric anesthesiologist is distinguished by doing an additional year of some specialty, what’s known as fellowship training, specifically in pediatric anesthesia.

Bill: What is the difference then between a pediatric anesthesiologist and somebody who just administers to adults?

Dr. Siegel: Right. It’s a really important question. For parents that are listening that have that concern, let me see if I can give a good answer. The fact that there are pediatric anesthesiologists does not mean that someone who is not a pediatric anesthesiologist cannot take care of children. What we really need to distinguish between our anesthesiologist that may have a diverse practice and that they take care of children as part of their practice versus, perhaps, an anesthesiologist that never takes care of children, and compare either of those two to an anesthesiologist who either exclusively takes care of children or has special expertise in taking care of, again, not necessarily a healthy child but a child with special concerns, special needs, special medical issues, or medical problems, including very small children such as a newborn infant or even an infant that’s maybe only a few months of age.

Bill: Okay. What are some of the special considerations when administering anesthesia to a child?

Dr. Siegel: There’s a number of differences. Obviously, children are not just small adults. They have certain special needs that are dictated by their anatomy and their physiology. Those are things that a pediatric anesthesiologist or someone that practices a lot of anesthesia on children would be familiar with. There’s differences in things such as the amount of oxygen that an infant may need or the doses of the medications or the kinds or amounts of fluids that are administered. There’s certainly differences in the vital signs and the way that we assess the well-being of the child as compared to an adult. So, there’s any number of parameters that are going to be different. And again, even within the pediatric population, we distinguish between, let’s say, newborn infants, infants under six months of age, and perhaps toddlers up to two years of age. Even within the pediatric population, it’s multifaceted in terms of the care and the kind of care that’s administered.

Bill: So, even within anesthesiologists, there could be somebody that specializes in a baby that’s under six months old compared to a child that’s five years old.

Dr. Siegel: Okay. That’s a fair question. I think you’re hitting on, really, the best answer for parents that are concerned about providing anesthesia care for their child. I would say, for the most part, if you have as a particular example, an otherwise healthy five-year-old for a tonsillectomy, you can be comfortable if you know that the hospital that you are going to has anesthesiologists that frequently care for five-year-old children and are comfortable caring for five-year-old children. You do not have to seek out specifically a pediatric anesthesiologist. If you so choose to, obviously that’s within anyone’s right to do so. But it’s not necessarily a necessity. However, I would say, I think most people would agree that children under two years of age—certainly, children under six months of age, and without question, newborn babies and, certainly, premature babies or infants in the neonatal intensive care unit—probably, under most circumstances, a parent would want specifically a pediatric anesthesiologist caring for those children.

Bill: All right. Excellent. I think that’s really important. Your advice or your suggestion is then for children under two years of age, certainly under six months of age or certainly, premature babies, that’s where a pediatric anesthesiologist, you would say, that’s when you need to look for one of those, correct?

Dr. Siegel: I would say that’s where a parent might gain an additional level of comfort. In terms of the qualifications of the anesthesiologist, again, understanding that board certification or where someone trained are important factors, that’s not the entire picture. There are certainly anesthesiologists that did not go to a pediatric fellowship that have been taking care of children for years, especially perhaps in underserved areas, where they don’t have the luxury of having a pediatric anesthesiologist who may be very competent in taking care of these children. But as a broad rubric, yes, the qualifications that we’re talking about are the starting point where parents can start to look. To add to the picture, understand that things completely change when you go from an otherwise healthy child to a child with perhaps a severe illness or a severe injury or some kind of complex congenital or acquired disease or special syndrome or involved in complex surgery, or a situation where the child needs a high level of intensity care pre-operatively and post-operatively. Those are all going to be mitigating factors in terms of a parent’s decision to decide whether or not their local hospital or their regional hospital provides them with the level of comfort that they’re looking for if they have to look outside of that scenario.

Bill: Absolutely. Okay. Very, very good. As a parent, how shall I ask for a pediatric anesthesiologist? Is there something I should say or somebody I should look for? What should I look for in a hospital? Is there a way to find that out? As a parent, where do I go to find a pediatric anesthesiologist?

Dr. Siegel: There are two issues. One is asking the question. Two is what you do with the information when you get the answer. It’s probably not difficult to get the information as long you ask, whether it’s the website of the hospital or whether it means calling the department of anesthesia and asking to speak to someone. Or a great resource would be to ask the surgeon, especially the pediatric surgeon that we’re talking about. Especially, in today’s day and age of the Internet, I don’t think it would be difficult for most parents to find out about the facility of the hospital that they’re either thinking of using or that they’re looking for, and there’s certainly all kinds of resources regarding anesthesia on the Internet. To name a few, specifically for our discussion, there’s the American Society of Anesthesiologists; there’s the American Academy of Pediatrics that has a subdivision on anesthesia; there’s an organization known as SPA, which is the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia. All these websites will give information on what a parent is looking for and what criteria they should look for, under what circumstances. But in relatively straightforward or simplistic scenarios, again, ask the surgeon, ask the facility, go on the website. That’s certainly a starting point. Now, it gets a little more complicated if the parent doesn’t really know what to do with that information and whether or not they should be satisfied that their child is being well-cared for. And a parent can ask for each facility for each scenario what the criteria are that the institution has in terms of who takes care of the children in the operating room, because every institution has criteria that will determine which anesthesiologists are taking care of the children.

Bill: I got you. Okay.

Dr. Siegel: Again, to reiterate, certainly ask the surgeon who’s involved, and be ready with that question probably at the first visit, because the day of, when you show up at the hospital for tonsils or for your hernia repair, whatever it might be, is not the time to start saying, “Well, I want a board-certified pediatric anesthesiologist.”

Bill: Right. Okay. I got you. So, in our last minute here then, what would you say to the parents of a child who is about to undergo surgery and require anesthesia? What’s your best advice for them?

Dr. Siegel: Stay calm, because the children pick up on the parents’ anxiety. If the parents are anxious, if the parents are worried, if the parents are upset, the children are going to be even more so, and the children are going to know that there’s something up, that there’s something that they need to fear, that they need to be worried about. And the parents need to communicate with the children. Each to its own, but the parent really needs to—if the child can handle it—to explain to the child what’s happening. And certainly, don’t hide things from the child. Children don’t like to be surprised, and honesty usually works as long as it’s done gently.

Bill: Absolutely. Great advice, Dr. Siegel. Thank you so much for your time today. We really appreciate it. For more information on Saint Peter’s, please visit saintpetershcs.com. This is Saint Peter’s Better Health Update. I’m Bill Klaproth. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Melanie Cole MS

Additional Info

- Segment Number 3

- Audio File st_peter/1430sp2c.mp3

- Doctors Hiatt, Mark

- Featured Speaker Mark Hiatt, MD

-

Guest Bio

Mark Hiatt, M.D. is a Neonatologist and Director of The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

The Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital.

For more information about Saint Peter’s Healthcare System -

Transcription

Bill Klaproth (Host): The neonatal intensive care unit or NICU at the Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital is one of the most experienced and one of the largest specialized facilities of its kind on the East Coast, with 54 intensive and special care bassinets. Preemies require a special brand of care, and the parents of those premature infants are often faced with numerous unknowns. Here to talk more with us is Dr. Mark Hiatt, director of the NICU at the Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital. Dr. Hiatt has spent more than three decades in the care of these most fragile newborns. Dr. Hiatt, thank you so much for being on with us today. So, tell us, what is a neonatal intensive care unit and what special features does it provide?

Dr. Mark Hiatt (Guest): A neonatal intensive care unit is a facility inside a hospital where there’s specialized equipment and specialized staff who are trained in taking care of newborn infants who have any medical or surgical problem. It’s important to understand that there are different kinds of neonatal intensive care unit, and the American Academy of Pediatrics has established a system whereby you grade these neonatal intensive care units by the depth and breadth of their facilities. The highest level is a level four neonatal intensive care unit that is equipped to take care of any possible problem, and our NICU here in New Brunswick at Saint Peter’s is a level four neonatal intensive care unit.

Bill: Okay. How would somebody know, an average parent or somebody that’s pregnant or somebody that needs to know this, how would they find that information out?

Dr. Hiatt: Probably the easiest way to do it is to discuss it with their obstetrician or the specialist that’s delivering their child. The obstetrician can make an assessment of what that particular family’s needs are. And if something has been discovered during the course of a pregnancy that would require either high-risk maternal care or particularly high-risk newborn care, the obstetrician be well aware of the kinds of facilities that are in their area and where they have delivery privileges, and they direct the patient to the appropriate facility.

Bill: Okay. I got you. So now let’s talk about -- you mentioned high risk in there. Let’s talk about high risk. Is little birth weight the only reason a baby may spend time at the NICU? Or what are the other ones as well?

Dr. Hiatt: As I said, Bill, we really have the capability to take care of any brand new baby who has any kind of medical or surgical problem. Low weight babies only comprise about 40 percent of our admission. The other 60 percent are larger babies, full-term babies whose mothers either have certain medical problems—for instance, diabetes or something like lupus—or the babies have medical problems. By all these attention over the years on taking care of low birth weight infants and extending their survival, the people in my field have learned a lot about newborn medicine and newborn physiology, and we’ve been able to raise the level of care for all infants.

Bill: Okay. So what percentage then of all babies born land in the NICU?

Dr. Hiatt: Overall in the country, about 1 percent of babies are extremely low birth weight—that is, under 1,500 grams. We’re talking about four million births. That’s not an insubstantial number. Overall though, about 8 to 10 percent of babies may be candidates to be admitted to neonatal intensive care units, usually for a shorter time than those smaller and usually more ill infants.

Bill: What are the causes of low birth weight? Getting back to that, is there any prevention through rest, diet, or medication?

Dr. Hiatt: Well, Bill, you have to differentiate between low birth weight due to prematurity and low birth weight due to some impact on the normal growth of the fetus in utero. Most cases of cases of low birth weight—and that we define under 2,500 grams—are due to babies being born earlier. The earlier you’re born, the less you’re going to weigh. But there are a cohort, a group of babies who come to our unit who may not be premature but yet they have low birth weight based on some impairment in their growth, either due to decreased blood flow or maternal high blood pressure or some other complication in the mother. As far as preventing low birth weight, you have to look at preventing, looking in both of these causes of low birth weight. As far as prematurity, there has been some effective intervention in lowering the instance of prematurity, but we don’t understand all the causes. So obviously, we haven’t been unable to eliminate it. There’s a drug that’s being used. Progesterone is being used in the group of women who have short cervix. Those women would usually deliver early, but now, with the use of this drug, that’s been a major change, and we’ve been able to prolong pregnancy. Some early deliveries are due to infection, and effective treatment can prolong the pregnancy. But overall, we just don’t have a magic treatment yet to prevent all premature delivery.

Bill: I was just going to say, so in either case, no matter what the cause of a low birth weight baby, is there an effect on development later on in a child’s life, or is that random? Is there any way to know that?

Dr. Hiatt: There are many ways to know it. I think that the takeaway message is that the vast majority of our children who come through neonatal intensive care unit, even the ones who are born very early, go on to lead productive lives and, for the most part, fulfill their biologic potential. We usually can get some indication while they’re in the hospital of what their prognosis is. We’re not yet at the point where 100 percent of our graduates go on without any complications, but I can -- I’m proud to tell you and I’m very gratified that every year, that’s getting to be a smaller percentage of those children who go on to have problems later on in life and those problems sometimes can affect the way children move. There’s something called cerebral palsy. The way that their minds work, there can be cognitive impairments. But fortunately, those are less common than they were, and they’re getting to be almost rare.

Bill: That’s very good news. Let’s talk about the parents for a little bit. It’s got to be very difficult for a parent whose child may be in the NICU for a long time. How do you help the parents deal with that, who may have to spend weeks or even months at the hospital?

Dr. Hiatt: Well, this is one of our major challenges. It is extraordinarily disruptive, both physically and mentally and emotionally, financially, on parents who normally would expect to take their brand new baby home after two to three days. Now we have an artificial situation where they’re separated from their child for weeks, sometimes months. They may have other children they have to take care of. The mothers themselves may not feel well. We have a lot of work to do to try to help them. We have a specialist on staff, social workers, psychologists, nurses. All of us are focused to try to ease this transition and make this situation a little bit more tolerable for the parents. One of the things that Saint Peter’s has done in the last six months is develop a system or purchase a system called the NicView System. This is a terrific addition to our equipment. This is a camera that, in real time, allows the parents to look at their infants in the NICU on any one of their devices, whether it’s their smartphone, their iPad, their computer. They have 24-hour access to their infant. And if they go home, they can just pull up their child’s picture on the screen, see what’s going on, call the nurse if they have any questions. We’re one of the only few hospitals that has this, and we really are fortunate because we’ve got a lovely grant from the Provident Bank Foundation to purchase this system, and I think it’s been a game changer for us.

Bill: Well, we are very fortunate to have level four NICU units like you have there at Saint Peter’s there to take care of our most vulnerable young children, and we thank you for that. Dr. Hiatt, thank you so much for your time today. We really appreciate it. For more information on the NICU at Saint Peter’s, please visit saintpetershcs.com. This is Saint Peter’s Better Health Update. I’m Bill Klaproth. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Bill Klaproth

Additional Info

- Segment Number 2

- Audio File st_peter/1430sp2b.mp3

- Doctors Singal, Dinesh

- Featured Speaker Dinesh Singal, MD

-

Guest Bio

Dinesh Singal, M.D., a cardiologist and director of the Cardio Metabolic Institute at Saint Peter’s Healthcare System, in Somerset, N.J.

For more information about Saint Peter’s Healthcare System -

Transcription

Bill Klaproth (Host): Physical fitness and maintaining a proper weight are key elements in the prevention of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But getting started with managing one’s weight plus staying on track once a regimen is developed can prove to be difficult for a great many people. With us is Dr. Dinesh Singal, a cardiologist and director of the Cardio Metabolic Institute at Saint Peter’s Healthcare System.

Dr. Singal, thank you so much for being on with us today. First off, how are diabetes and cardiovascular disease linked?

Dr. Dinesh Singal (Guest): There are many reasons by which people get cardiovascular disease. We call them, traditionally, risk factors. Diabetes is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In fact, it’s such a potent risk factor that in our current guidelines, we assume that all diabetics already have heart disease and when we go to treat these folks, we treat them as if they’ve already had heart disease. It’s a really potent risk factor for this disease.

Bill: Okay. Let’s talk about diabetes then for a quick second. How would somebody know if they have it? Are there warning signs or symptoms that people should be watching out for?

Dr. Singal: Yes. From a symptoms standpoint, if someone starts losing weight, they have excessive urination which is unexplained, or they start feeling very thirsty, those are some of the clues by which they may realize and find out that they’re diabetic. But that’s usually when it’s fairly extreme. Most of the times, we pick up folks a lot earlier by doing routine blood tests. If in a fasting blood test, someone’s sugar is greater than 126 – or there’s another test called Hemoglobin A1c and if that’s more than 6.5, then that is diagnosed as diabetes.

Bill: What is the percentage of the population who is at risk for these conditions?

Dr. Singal: There’s an organization which puts out a report in a national level and they just came out last month for data from 2012. What they found was that in 2012, about 29.1 million Americans, almost 9.3% of the population had diabetes. In addition, there’s a condition called pre-diabetes when the numbers are somewhere between normal and toward the number that I just quoted. That population is almost a third of the US population. In the older population over 65, it’s almost close to 50% people are pre-diabetic.

Bill: Wow. And you said diabetes is kind of a precursor to cardiovascular disease or they’re at a higher risk for cardiovascular disease. Is that right?

Dr. Singal: It’s actually one of the most important and major risk factor. In the recent guidelines for cholesterol management, we very aggressively managed people who have underlying cardiovascular disease. What we found out was, like I said earlier, in diabetics, the incidence is just so high that we are as aggressive in lowering the cholesterol because the risk is just as significant. We treat diabetics almost as if they have underlying disease.

Bill: Okay. Let’s talk about lifestyle now. How does lifestyle a factor in the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease?

Dr. Singal: The reason diabetes has become an epidemic all over the world is, in large part, because of lifestyle. Our exercise amount have decreased. People live in the suburbs where they are used to driving from one point to another, walking has reduced, so with that, folks wind up gaining weight. Eating habits for a lot of people are not very good. They wind up eating high glycemic index foods which aren’t metabolized as fast. Between all of that, folks tend to gain weight and obesity is a major precursor for diabetes and along with that come a whole host of medical issues which add to the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Bill: Right. Our current hectic, modern lifestyle certainly doesn’t put us on a good position for this. You mentioned exercise. It’s obviously very important. But why is it that exercise safeguards against the development of these conditions?

Dr. Singal: Exercise plays many roles in a variety of ways. One, it allows us to burn more calories so the food we are eating actually has the chance to get burned and so weight is better controlled in someone who exercises regularly. It also improves the resistance to disease. We’ve seen over and over again, people who exercise regularly tend to have lower blood pressure than folks who don’t. Their lipid numbers are better, so the cardiovascular disease burden has reduced.

People’s moods are better when they exercise more, and those people have been, again, shown to have better outcomes in the long run. It also boosts energy by improving the metabolism, so a person who is more active actually feels more energetic than someone who is less active. People sleep better when they exercise and that also has a direct correlation with blood pressures when we are awake. Overall, exercise is fun and, with all these other factors, lead to a healthier lifestyle and a longer life.

Bill: Right. It’s just good for you, darn it, right?

Dr. Singal: That’s right.

Bill: We just all need to jump in there and do it. Diet and exercise are always linked. How does diet factor for the development and containment of these diseases?

Dr. Singal: Diet plays a major role because what we eat and how much we eat translates into all these things I just said earlier. There are foods which have so-called higher glycemic index, the starchy foods – potatoes, rice, bread, desserts, sweets. All these items tend to get converted to glucose and sugar much quickly, and the body only has a certain capacity to handle all that. When there is excess, then it all builds up in higher glucose and more predisposition to diabetes, higher lipid values.

And also the amount we eat, when you go to a restaurant, you have to make choices. This same item with some extra cheese can add a lot more calories than we need. Both the choice and the kind of food and the amount of food adds up and that then results in, again, what I said earlier, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, high lipids. Choice of food and how much we eat is extremely important in our wellbeing.

Bill: Okay. Let’s break this down a little bit farther for our listener. Give me, if you just briefly, the best exercises to do.

Dr. Singal: Well, the best exercise, at least, from a cardiovascular standpoint is aerobic exercise. The goal is to move our limbs, move our body. It could be whatever one is in a position to do based on their age and their overall condition. It could be a brisk walk, if a person can jog and run, bicycling, joining a Zumba class, Pilates. It needs to be fun and it needs to burn calories. Having said that, in addition to the aerobic piece, one needs to exercise most of the group muscles, so lifting some weights and some resistance activities are also useful. And it needs to be at least three to four times a week. Studies show at least a half hour, so the heart rate can go up and be sustained for at least that period of time.

Bill: Okay. Got you. That’s excellent. Pay attention to aerobic exercise – walking, jogging, biking, take a Zumba class. Pay attention to group muscles at least three to four times a week. All right, let’s do the same now with diet. What would be the best type of foods to eat then?

Dr. Singal: From a food standpoint, fruits and vegetables are the best bet. They give us fiber, they are less in calories, they are natural. Any kind of processed food has to be limited. Foods which have high glycemic index, like I said before, potatoes, rice, bread, pasta, desserts, they need to be in a lesser quantity, and a balance between protein. We obviously need some fat and some carbohydrates. Some of these fad diets where one is doing one extreme over the other, when studies have looked at it, they find that it really don’t do any better than just a reasonable calorie, well-distributed diet with a higher amount of vegetables and fruits and some nuts. That should be the focus, with a reasonable composition of proteins, white meat rather than red meat, less egg yolk (the yellow of the egg). So fruits and vegetables, again, need to be the bulk of one’s diet.

Bill: Excellent. In our last minute here, what is your best advice then for somebody to maintain the diet and exercise regimen? We know what exercise to do, we know what to eat, how do we stick with it?

Dr. Singal: One needs to find an activity which they enjoy doing. What we’ve discovered at the Cardio Metabolic Institute is that when we do activities in groups, people tend to sustain those more than when they’re trying to do it by themselves. The goal has to be to get to a certain point, but it can’t be achieved in one day. If somebody isn’t used to doing it, they start slow and work their way up. If they can maintain something for about a month or two months, they’ll find it isn’t that difficult. The first month or two months to change habits, to change lifestyle, is the toughest piece. Once you get past that, you can maintain it for a long time to come.

Bill: Sounds great. Dr. Singal, thank you so much for your time today. We really appreciate it. For more information on Saint Peter’s, please visit saintpetershcs.com. That’s saintpetershcs.com. This is Saint Peter’s Better Health Update. I’m Bill Klaproth. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Bill Klaproth

Additional Info

- Segment Number 1

- Audio File st_peter/1430sp2a.mp3

- Doctors Zakir, Ramzan

- Featured Speaker Ramzan Zakir, MD

-

Guest Bio

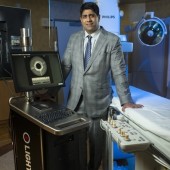

Ramzan Zakir, M.D., is a specialist in cardiovascular disease. He is one of the first physicians in the Northeast to be trained and licensed in the use of Lightbox technology for the treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD). Zakir performs more than a dozen cardiac procedures, including cardiac catheterization and angioplasty. He is a 2002 graduate of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey medical school.

For more information about Saint Peter’s Healthcare System -

Transcription

Bill Klaproth (Host): There is a new weapon in the treatment of peripheral artery disease or PAD. Peripheral artery disease is a common circulatory problem that can affect feet and lower legs and may lead to amputation. But there’s a new breakthrough: a minimally invasive lumivascular technology called Lightbox that is now used to treat it. Saint Peter’s University Hospital is the first and only hospital in central New Jersey to have it.

We are pleased to have Dr. Ramzan Zakir, cardiologist and director of the peripheral vascular program at Saint Peter’s with us. He is one of the first physicians in the northeast to be trained and licensed in the use of Lightbox technology.

Dr. Zakir, thank you so much for being on with us today. So, let’s get right to it. What is PAD or peripheral artery disease?

Dr. Ramzan Zakir (Guest): Peripheral arterial disease is one of the cardinal manifestations of atherosclerosis. We’re all familiar with atherosclerosis. It’s when you have a plaque buildup in the arteries. In the heart, it could lead to chest pains and it could lead to heart attacks. In the legs, when you have plaque build-up, it reduces the flow to the feet and this could lead to excruciating pain when one walks. When one walks a certain distance, they have to stop due to excruciating pain and that’s called claudication. Other manifestations of peripheral arterial disease, more in the later stages, is if a patient were to have a wound and if there’s decreased blood flow, that patient could be risk for amputation if the blood flow is not restored.

Bill: So, you’re talking about pain in the feet. Can you describe that a little better? Is that in the heel or the whole foot or the whole lower leg? Just so somebody who may be listening can determine, “Maybe this is me.”

Dr. Zakir: Right. It depends on the location of the blockage. The areas where there’s complaint of pain is in the buttock area, the thighs, and the most common places, in the calves. Then a later manifestation is in the feet, when the feet hurt all the time.

Bill: Does it feel like a cramp when you’re talking about the calf or the buttocks? I mean, does it feel like a cramp or is it just a sharp pain?

Dr. Zakir: It’s more of a dull pain. It’s an excruciating pain. It’s a pain that occurs during exertion and it’s usually reproducible, in the sense that once you walk a certain amount of distance, that patient that has that pain has to stop for a little bit more and then can walk a little bit more and gets the pain again. Usually, the patients will tell you, “Every time I walk half a block, I have to stop because of the pain.”

Bill: PAD really hinders the quality of life for patients then?

Dr. Zakir: Exactly. Because these people that were active and they were able to partake in the normal activities now find it very difficult to do so.

Bill: Is that the usual telltale sign: a short distance and you’re feeling this excruciating pain in such a short walk?

Dr. Zakir: That’s the typical, classic presentation. Unfortunately, a lot of patients who have PAD are asymptomatic or have atypical symptoms, but the classic description is exactly that as you just described it.

Bill: Okay. Now, how is it typically treated? Before we get to Lightbox, how was it treated before?

Dr. Zakir: The first line is medicines and exercise. There are some drugs that do improve the ability to walk a little bit more. And then, traditionally, it was a surgical bypass that was performed. However, it’s a very invasive procedure associated with some mortality and morbidity and infections. And now, what’s becoming more and more common is a catheter-based procedure to open up the blockages. It’s a same-day procedure; it’s just a little catheter goes in the groin and we’re able to open up the blockages in a minimally, non-invasive way.

Bill: Is that what the Lightbox treatment is then?

Dr. Zakir: Lightbox is a way to treat with the endovascular, with the catheter-based therapy. A lot of times, these patients have what we call a chronic total occlusion. That’s when the artery is totally blocked. It’s not narrowed. Significantly, the artery is totally blocked and the artery in the leg, it could be blocked for a long portion of the leg. To open it up with the traditional approach with the catheter and the wire could be difficult because we’re kind of poking the wire and we’re kind of hoping we go in the right direction; we’re kind of navigating in the dark. That approach is pretty good but we’re always working on trying to improve our methods of opening up these blockages. What the Lightbox does, it has what we call an OCT fiber which emits light waves at the tip of the catheter and we’re able to see what’s inside the artery, so when we’re trying to open up these long, total blockages, it makes it a lot easier and safer to open up these blockages. Once we’ve crossed the total blockage, then we can balloon and stent and treat the patient to improve the patient’s symptoms. But the first line …

Bill: Go ahead.

Dr. Zakir: The problem is crossing the blockage. With the traditional approach, the failure rate could be from 13% to 34%. In the study looking using the Lightbox and this Ocelot catheter success rate was up to 97%. We’re improving our ability to cross these blockages and improving safety as well.

Bill: So, it seems like there is really twofold benefits to the Lightbox technology. One is it’s minimally invasive because you don’t have to surgically go into the leg to get to the diseased artery. Two is it’s a lot more effective because you’re going right into the vein that is clogged and you’re able to unclog it basically with the light at the end of your device there.

Dr. Zakir: Exactly. You’re able to image and you know exactly where you are, so you’re able to navigate the catheter towards the plaque, towards the blockage and away from the healthy part of the artery. Because when we do it the traditional approach, we’re poking around and we’re hoping we’re going in the right direction. This way, we know we’re going in the right direction.

Bill: You probably have much less recovery time as well.

Dr. Zakir: Right. The recovery time from these endovascular procedures, often, we close the artery and patients are walking two hours after the procedure. Most of the time, it’s a same-day procedure. They go home the same day.

We did a case just a few days ago. Patient had pain for five years and we did the procedure. We used the Lightbox, we’re able to get through, deliver definitive therapy, balloon stent. He got up, he walked off the table. Two hours afterwards, he was walking. The next day, we got a call that he’s able to walk with the pain totally gone. It changed his life.

Bill: Amazing. He’s probably able to walk around the block for the first time in a long time.

Dr. Zakir: Right. Exactly. It’s a life-changing experience.

Bill: Absolutely. So, how long does this last for then? Is this like, “Hey, you’re good for five years or ten years?” Is there any kind of way to tell so far?

Dr. Zakir: That’s a great question. That has more to do with just if we stent or if we balloon. Re-stenosis rates are higher; re-stenosis meaning getting blocked up again. It’s higher for the legs than it is for the heart. But on the horizon we have excellent treatments coming down the pipe with the drug-coated balloons, even bioabsorbable stents and even drug-eluting stents. The technology is getting better and the ability to stay open is improving. We’re even getting better on that end as well.

Bill: That is terrific. In our last minute, Dr. Zakir, what is your best advice to someone who feels like they may have PAD?

Dr. Zakir: To go to their primary care doctor. Then they can just further work it up with the initial test that’s usually what we call an ABI, an ankle-brachial index—that can give an idea if there’s PAD or not—and then from there, a referral to a specialist.

Bill: Sounds good. Dr. Zakir, thank you so much for your time today. For more information on PAD, please visit saintpetershcs.com. That’s saintpetershcs.com. This is Saint Peter’s Better Health Update. I’m Bill Klaproth. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Bill Klaproth

Additional Info

- Segment Number 5

- Audio File virginia_health/1429vh5e.mp3

- Doctors Liu, Kenneth

- Featured Speaker Dr. Kenneth Liu

-

Guest Bio

Dr. Kenneth Liu is a fellowship-trained neurointerventional surgeon who specializes in caring for patients with aneurysms and stroke as well as brain and spinal vascular malformations.

-

Transcription

Melanie Cole (Host): Pseudotumor cerebri can cause symptom that resemble a brain tumor but is different from that. My guest is Dr. Kenneth Liu. He’s a fellowship-trained neurointerventional surgeon who specializes in caring for patients with aneurysm and stroke, as well as brain and spinal vascular malformations at UVA Neuroscience: Brain & Spine Care. Welcome to the show, Dr. Liu.

Dr. Kenneth Liu (Guest): Thank you, Melanie.

Melanie: So tell us a little bit about pseudotumor cerebri.

Dr. Liu: Pseudotumor is a condition that no one really knows a lot about it. What it basically is is a patient will present with increased pressures in their brain and can develop symptoms of severe headache. They can develop visual loss, and they can have a ringing in their ears. But it can be a fairly debilitating condition.

Melanie: People are going to have some of these symptoms, and right away they’re going to think that they have a brain tumor. It can be very scary. What red flags would people have that would send them to see you?

Dr. Liu: I think typically these patients first go to either their family physician. And with someone who’s demonstrating symptoms of increased pressures in their brain, such as headaches and maybe visual loss, the doctor will usually have them see an ophthalmologist and also undergo some non-invasive brain imaging. Typically, the brain imaging will be fairly normal—no tumors, no aneurysms, nothing scary, anything like that. And when the eye doctor looks into the patient’s eyes, they’ll see pressure behind the eyes or fluid built up behind the eyes. In those sorts of situations, you can almost diagnose the patient with pseudotumor at that time. Typically, I’ll get involved at that point.

Melanie: What are some risk factors for pseudotumor?

Dr. Liu: Now, that’s a really great question. I don’t think anyone really knows the answer to that question. A lot of patients with pseudotumor tend to be young female patients from about age 20 to 35, 40 years old. They do tend to be overweight. But I do see patients with pseudotumor that are the complete opposite of that. They’re male, they’re older. So I think that there does tend to be a population of patients who can get this, but it really can affect everyone. Some people think that if you take too much of Vitamin A, you can get pseudotumor, but I don’t know that that’s really been proven.

Melanie: So, Dr. Liu, is pseudotumor an emergent condition? If people would come to see you, you would diagnose this. Is this something emergent that you have to do something about very quickly? Can it predispose someone to stroke or other problems?

Dr. Liu: Generally, it’s not an emergency condition, but it’s a condition I think a lot of physicians can be fooled by it because it appears benign. The result of imaging is normal and there’s no tumor, there’s nothing to worry about, but the reality is that these patients do indeed have high pressures inside their skull, high pressures inside their brain, which can lead to permanent visual loss. So it is something that should be investigated in a fairly aggressive process. And there have been patients, I’ve had patients who do present in a very emerging fashion who do need to go under treatment right away to decrease the pressures in their head and to save their vision.

Melanie: Tell us about treatments, Dr. Liu. What treatment options are available?

Dr. Liu: A lot of the more traditional treatment options for pseudotumor are aimed at trying to get the pressures in the head to come down. Traditionally, there haven’t been a lot of great ways to do that. Typically, patients will often experience relief when spinal fluid is drained from their brains, so either they undergo a spinal tap or have some kind of drain placed and some fluid is taken off. Typically, that will give them some temporary relief. A lot of times, when patients get relief from that, neurosurgeons such as myself, will put in something that’s called a shunt, which is basically a permanent drainage system that drains spinal fluid from the brain to another spot in your body, such as the abdomen. While these shunts can be helpful, it’s really not treating the underlying condition, and about 5, 10 years ago, some of us realized that some of that there’s a subset of these pseudotumor patients that actually have narrowing in the veins that drain blood from the brain. What that narrowing of the veins does is it essentially causes a traffic jam in the brain and causes blood to back up, and that’s why the pressures go up. You can sort of imagine it similar to a clogged toilet. So a shunt, if you were to use that analogy, a shunt is something like if your toilet’s clogged, you kind of use a bucket or a cup to drain the toilet, which doesn’t really fix the underlying issue. One of the latest treatments that we’ve been pioneering here at UVA is using a balloon and a stent to minimally invasively open up these areas of narrowing. What that does is that improves the drainage of blood from the brain, decreases the traffic jam, gets rid of the blood backing up, and these patients will actually, their pressures will actually return to normal. A lot of times, their vision will improve and their headaches will get better as well.

Melanie: What about medications? Is there something in lifestyle changes, anything you want the listeners to know? And what kind of medications might they go on after this treatment?

Dr. Liu: There probably aren’t a whole lot of lifestyle changes that a patient can make. A lot of us will recommend trying weight loss initially, but I know that can be very difficult, and the results are variable with that approach. Some physicians will try to, before any kind of invasive treatments, some physicians will try a medicine called Diamox to try to decrease the amount of spinal fluid that’s produced. Again, that doesn’t really treat the underlying issue of potentially having veins that are narrowed veins or blocked veins that are causing the pressures to build up, and a lot of patients don’t really tolerate Diamox that well. It makes them feel very funny. As far as medications that someone might be on, after a stent is placed, anytime a stent is put in the body, whether it’s in your heart or your brain or your leg or anywhere else, a stent -- stents are made out of metal, and so, patients will typically need to be on a short course of blood thinners to kind of keep the blood lubricated while the stent heals into the blood vessel. And that’s the same thing that happens when you have a stent placed in a vein in your brain. You will need to -- typically, we have patients on two blood thinners. One is an Aspirin. The other one is a medicine called Pladex, which I’m sure that everyone has seen TV commercials for it. But typically, patients are on these for maybe three to six months after the procedure, and then we kind of start tapering them off at that point.

Melanie: Dr. Liu, why should patients choose UVA to receive treatment for brain conditions?

Dr. Liu: Well, I think the great thing about UVA is that I think you have a tremendous number of very smart, very bright people here that are leaders in their field, not only in neurosurgery but in areas such as radiology and endrocrinology, and almost every specialty there has… I know there are tremendously bright people there, and they are considered national experts. For something like pseudotumor, you have neurosurgeons, myself and my partner, Dr.Crowley, who are both trained, and we’re sort of the 21st century neurosurgeons. We’re trained in both open techniques and minimally invasive techniques and we’re able to tailor patients treatments to what we think is the safest and most effective treatment option. Then I have colleagues in interventional neuroradiology who also have a lot of experience placing stents in the brain. And so actually, I think here at UVA, not only do we have lot of bright people, but there’s a tremendous amount of collaboration, and I think we’re all very excited about figuring out things that we can do to push the field forward and give and provide what we think is the best care for patients.

Melanie: Thank you so much, Dr. Kenneth Liu. You are listening to UVA Health Systems Radio. You can get more information at uvahealth.com. This is Melanie Cole. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Melanie Cole, MS

Additional Info

- Segment Number 4

- Audio File virginia_health/1429vh5d.mp3

- Doctors Brown, Thomas

- Featured Speaker Dr. Thomas Brown

-

Guest Bio

Dr. Thomas Brown is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon who specializes in hip and knee replacements.

-

Transcription

Melanie Cole (Host): What symptoms would lead you to consider a hip replacement? What is the surgery and recovery process like? My guest is Dr. Thomas Brown. He’s a board certified orthopedic surgeon with UVA Orthopedics, and he specializes in hip and knee replacements. Welcome to the show, Dr. Brown. What are some symptoms that people would feel pain? What are some of the most common symptoms that would lead patients to even consider a hip replacement?

Dr. Thomas Brown (Guest): Good morning, Melanie. I think the most common symptom is pain that you experience in the front of the hip that may radiate down towards the knee. Sometimes the hip pain can be confused for back pain, but that’s really more on the backside, where people experience pain that’s radiating from their back. The other symptom that’s constant with hip replacement is stiffness. People that have difficulty putting their socks and shoes on, having a hard time getting down to the toes, that may suggest that their hip joint is now getting a little bit stiff and losing range of motion.

Melanie: So Dr. Brown, what question should patients ask their doctor when they’re considering a hip replacement?

Dr. Brown: I think the two most important ones are, number one, the frequency in which the orthopedic surgeon performs the procedure. I think that’s like any other procedure; the more you do it, the more proficient you become at it. So I think the literature shows that surgeons that perform more than 50 hip replacements per year are pretty good at it, so I think that’s probably a good place to start with your surgeon. Secondly would be what type of approach is used or different ways of getting into the hip joint, whether from the posterior or from the backside of the hip or from the lateral approach or, more recently, a direct anterior approach, which facilitates recovery a bit.

Melanie: Tell us a little bit about hip replacement. People are afraid, Dr. Brown, of getting a new hip, and as someone who has done their rehab so many times, I can tell you and tell them that this is one of the least recovery time, right? Tell us a little bit about the surgery and recovery time.

Dr. Brown: Yeah. Obviously, it’s a big operation, and people are understandably anxious about it, but it’s probably one of the most successful operations performed to alleviate pain and restore function.

Melanie: That’s what I’m saying.

Dr. Brown: I think probably one of the biggest regrets patients have is waiting before they have their surgery after they actually decide to proceed. But again, the recovery is fairly quick. We try to get people up, out of bed, on the day of surgery to do some walking, and normally, you’re able to put full weight on your new hip right away. The stay in the hospital can be as short as overnight to 2 or 3 days, depending on the circumstances and what type of condition people are in before the surgery. But the recovery and the pain relief is really quite striking and quite dramatic early on. People would often wake up from the surgery, and the deep pain they had from their arthritic hip is gone.

Melanie: How long does the surgery take?

Dr. Brown: Depending on the size of the patient and the complexity of the arthritis and the reconstruction required, it can be anywhere from 1 to 2 hours for a primary hip replacement.

Melanie: When people are experiencing this before, do you recommend, Dr. Brown, that they do some prehab before they’re going to get their new hip? Do you want them doing anything? People assume that once they’ve got a new hip, everything else is all perfect. Do you want them doing some things to the muscles that are going to surround that new hip?

Dr. Brown: That’s a great point. I think that the stronger and more fit you are coming into the operation, the easier recovery will be. I think that’s important that patients understand that even with an arthritic hip, you can still try to be active. And if you are experiencing pain prior to surgery, you’re not really causing any damage, but it’s good to strengthen the muscles beforehand, which actually will improve and speed up your recovery after the surgery.

Melanie: Now, are there some people who are not candidates for this type of surgery?

Dr. Brown: There are certain medical conditions that would prohibit performing hip replacement. And normally, we try to exhaust all non-operative treatment options for patients before resorting to hip replacement surgery, and that would include some physical therapy, some medications, and occasionally, an injection into the joint itself may provide some temporary relief for pain.

Melanie: People experience pain from osteoarthritis, from rheumatoid arthritis when they’re walking, when they’re moving, but what about if they’ve got that pain that continues while resting? Is that one of those kind of red flags that would send them to see you?

Dr. Brown: Yeah, I think usually that’s one of the factors that will finally make people decide it’s time to proceed with surgery when they cannot escape from the pain. I think everyone will start to curtail their activity, park the car closer to the grocery store, take the elevator instead of the stairs, and so forth, and do fewer things around the house. But once the pain permeates their rest and sleep time, then it’s hard to escape. I think that will be one of the deciding factors to consider having their hip replaced.

Melanie: Dr. Brown, what about weight loss? Do you encourage weight loss before this surgery or even afterward? Is somebody’s weight a factor in whether their hip gets degraded or not?

Dr. Brown: Absolutely. I think from a surgical standpoint, the lighter a patient comes in, the safer the entire experience is—from the anesthetic standpoint, from the surgical standpoint, the risks are lower if you come in at an ideal body weight. So that certainly is an important thing to consider before embarking on a joint replacement. From a standpoint of trying to avoid or postpone surgery, certainly, the lighter you are, the more stress you place on your hip joint. Just walking down the street, your hip is experiencing four to five times your body weight with every step you take, especially when you’re going up or down stairs. So even a modest weight loss of 5 or 10 pounds will have a big impact on the amount of force that the arthritic hip joint experiences, and that sometimes can make a difference in allowing people to put up with it for a longer period of time.

Melanie: How long do the hip replacement -- are they a lifetime thing? They last? When can people resume that normal activity—walking? What should they be doing?

Dr. Brown: Durability of the replacements is getting better all the time. I think historically, it was 10 to 15 years, but we have really very, very good techniques of fixing the prosthesis to the bone, which involves biologic fixation, where the bone actually grows into the metal and becomes a part of you, and that’s very durable. And also, the bearing surfaces—that’s what rubs upon what surface rub together—and we normally use either a metal or a ceramic ball with a hard plastic or polyethylene liner. There’s every indication that these may last for 2 or 3 decades. As far as when you can resume activity, it depends on the type of approaches used for the surgery. For certain techniques, it requires a short period of time where you are avoiding certain motions to allow the surgical approach to heal itself back up. Other approaches require a little bit sooner return to activity with fewer restrictions. But within three months’ time, people are back to doing most activities.

Melanie: Dr. Brown, tell the listeners why they should come to UVA for a hip replacement.

Dr. Brown: Well, as I mentioned before, I think experience and numbers are important, and I have two other highly qualified fellowship-trained joint replacement surgeons that work with me. We perform over 1,200 joint replacements annually here at the university. We’re one of the few centers in this area that is certified by the J-Co Certification Agency for Joint Replacement, and we also tackle many of the problems that occur, referred in from around the state for revision surgery. So we’re very careful dealing with almost any issue that arises, and we have a great staff, and I feel that we can get patients a very good opportunity to resume normal activity and alleviate their pain.

Melanie: Dr. Brown, in just the last minute or so that we have left, give patients your best advice for those considering a hip replacement, and maybe even what their families can do to get them ready for this.

Dr. Brown: I think probably the best piece of advice I can give is to learn more about the procedure. Do some reading. The Internet is a dangerous place to get information in terms of whether that’s going to be accurate or not, but I think there are good agencies such as the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and also the American Association of the Hip and Knee Surgeons, the Arthritis Organization. All these entities have very good information for patients to learn more about joint replacement. And then discuss it with your family, and most importantly, discuss it with your primary care physician and orthopedic surgeon as to whether or not they feel that they are an appropriate candidate for surgery and if not, what things they can do in preparation for surgery to make the whole experiences safe as possible.

Melanie: Thank you so much, Dr. Thomas Brown. You’re listening to UVA Health Systems Radio. For more information, you can go to uvahealth.com. This is Melanie Cole. Thanks for listening. - Hosts Melanie Cole, MS

Additional Info

- Segment Number 3

- Audio File virginia_health/1429vh5c.mp3

- Doctors Cherry, Kenneth

- Featured Speaker Dr. Kenneth Cherry

-

Guest Bio

Dr. Kenneth Cherry is a board-certified vascular surgeon whose specialties include arterial disease in athletes.

-

Transcription

Melanie Cole (Host): Most elite athletes are custom to experiencing a certain degree of muscle pain and fatigue during high-intensity exercise. Recently however, some athletes, particularly cyclists, have reported symptoms of leg pain and weakness from an unexpected cause. This could be a serious vascular condition. My guest today is Dr. Kenneth Cherry. He’s a board certified vascular surgeon at UVA Heart and Vascular Center whose specialties include arterial disease in athletes. Welcome to the show, Dr. Cherry. Tell us, what is external iliac arteriopathy?

Dr. Kenneth Cherry (Guest): Good morning, Melanie. It is a narrowing of the external iliac artery in essentially elite athletes. The external iliac artery, the aorta comes down in just about the level of the belly button and just in front of the spine, divides into the common iliac artery. Then that shortly divides into the internal iliac artery that feeds the pelvis and the external iliac artery. It takes blood down to the legs. In these athletes, the external iliac artery gets narrowed, and oddly enough, it’s just the opposite of all other vascular disease. It’s because they are in such good shape and exercise so much. In this country, we see it mostly in cyclists, but it can be seen in runners, triathletes. It’s being reported in ice skaters, power ice skaters, speed ice skaters. And it’s thought it’s because the external iliac artery is tethered there at the bifurcation, then these people are so fit. Their inguinal ligament is very taut, so there’s no sliding of the artery back and forth under the ligament as there is in less fit people. The other things that go with it, hypertrophy soleus muscle. It’s really the repetitive exercise. These cyclists will cycle anywhere between 5 and 20,000 miles a year, so many of them put more miles on the bicycle than people put in their cars. They’re also putting gallons of blood past their arteries quickly with their great hearts, so it’s a stretch injury, if you will, because when they bend over, they need to lengthen that artery and they can’t do it because of that taut ligament. It’s a bit of a stretch injury and then a flow injury also. I hope I didn’t talk too long on that.

Melanie: No, that was perfect. Dr. Cherry. It’s amazing to me because the public is used to hearing that if you’re in better shape, you’re opening up your arteries and clearing them out, and this is a narrowing. Who is particularly at risk? If you’re an elite cyclist, are you then going to be more at risk if you’re putting 15-20,000 miles on your bike? Does that give you more risk or are there certain predispositions that are going to make somebody at risk for this?

Dr. Cherry: Well, it’s an excellent question, and we don’t know the answer yet. Because you could ask, “Why didn’t Lance Armstrong get it? Why didn’t other truly elite athletes get it?” And who does and who doesn’t, we don’t know yet. But we know that cyclists are seeing, speed skaters, runners, and these people are who truly fit and really put themselves up to the limit. One of the things that we, that a radiologist in here and I have sort of independently come to the conclusion is that those cyclists who have very short common iliac arteries, where their external iliac artery begins high in the pelvis, that seems to be starting to be a more prominent theme, and so we’re looking into that right now. But it’s very seldom seen in less than elite athletes. Sometimes a very high-performing amateur can get it, but it’s not very frequent.

Melanie: Dr. Cherry, how’s it treated? What do you do and what symptom? So they come to you with this claudication with this leg pain. They don’t know why. They can’t explain it. They assume it’s probably muscular or something like that. What do you do for them?

Dr. Cherry: Well, if indeed they have it and we bring them in and we put them on bicycles, they bring their pedals and we have a cycle, and they cycle until they get their symptoms. We have measured the pressure in their arteries before, and then we do it immediately afterwards to see how far it drops. Invariably, if they have it, it will drop. And then we get specialized our arteriogram, where they put a catheter in their artery and they take a picture. That’s done with the patients supine, lying on their back, as it is with all patients. But then we have these patients flex their hips for the stress position they’d have cycling, and that will accentuate any abnormalities they have. If we see the abnormality and they wish to proceed, then we will go ahead and perform an operation. If it’s localized and early in the state of this disease, we can do what’s called a patch angioplasty; sew a piece of plastic artery over that area with or without an endarterectomy, where we clear it out. It’s an interesting arterial problem because it involves all the layers of the wall. It’s not just the inside of the wall of the entire artery; all three layers are involved. If it is more extensive, then we’ll replace that part of the artery with a bypass graft. And we’re also relaxing the inguinal ligament with the small incision there and hope don’t recapitulate the injury later.

Melanie: Well, that would certainly be the goal so our athletes are able to return to their peak performance, unless they’re ready to settle down into a sedentary lifestyle, Dr. Cherry. This current treatment, this is what you’re doing. Are they able to return to their lifestyle that they have?

Dr. Cherry: The majority, around 85 percent will go back to their peak performance or performance they’re happy with. There’s been one of my patients who’s spending the last two Olympics in bicycling and has done well, and there are others that do well. Some don’t do as well, and some of it has to do -- you know, if I’d do the same operation and a 70-year-old who needs it because they can’t walk to the grocery store, they’re having [rest] pain, I probably have all sorts of leeway in the link so I can make that graft. With these very elite athletes who are putting these grafts to such stress, I have much less leeway. If you make it too short, they’ll narrow where you sew it in. It’ll pull taut there. If you make it too long, it will kink. So there’s a very narrow window in there to get the length right. And I think that has a lot to do with it also, with those that don’t recover fully.

Melanie: Do you have any advice for athletes when you first meet them? They’re worried because this is a lifestyle that they’ve developed and that they are used to. Do you have any best advice for them either before or after the surgery what they should be doing differently?

Dr. Cherry: Well, we used to have a physical therapist here who’s a very avid and very excellent cyclist, and I would link him up with these patients when they came. Because of his knowledge of bicycling and his interest in it, some of these people, he could spot and say, “Well, you know, they had their pedals fired too far forward, or, “The seat height wasn't right.” One of the things that we do, especially if it’s early, is have them work with a trainer to see if some adjustments in the seat height, where the pedals are, their mechanics might make a difference. There are some things that I’m not clever enough myself to spot, but people who deal in that, the physical therapists and the trainers can. Then it becomes a question of how much they wish to proceed. Many of these people don’t have to go to a sedentary lifestyle, but if they didn’t want the operation, would have to accept a less strenuous lifestyle. And for these young people who’ve made it their lives, that’s a hard thing to do, so most of them wish to proceed.

Melanie: Dr. Cherry, other than the fact that you are one of the nation’s foremost experts on this condition, why should someone come to UVA for their treatment?

Dr. Cherry: Well, I think because we’ve seen that it’s a rare condition. I get calls from people all the time say, “Well, we’ve got the arteriogram and they don’t have it.” Yet when we review the arteriogram, they do have it, because they’re at first subtle changes that you see. As I say, I think over the course of time, it’s like anything. If you do enough of it, you pick up subtleties and nuances that you didn’t realize just a few years ago. We published a paper about 2 years ago on this, and many of the things that we do then, we have changed subtly in the time period because of a number of patients we see. So I think that’s the benefit.

Melanie: Well, thank you so much, Dr. Kenneth Cherry. You’re listening to UVA Health Systems Radio. For more information, you can go to uvahealth.com. This is Melanie Cole. Thank you so much for listening. - Hosts Melanie Cole, MS

Additional Info

- Segment Number 2

- Audio File virginia_health/1429vh5b.mp3

- Doctors Corbett, Sean

- Featured Speaker Dr. Sean Corbett

-

Guest Bio

Dr. Sean Corbett is a fellowship-trained pediatric urologist whose specialties include caring for a wide range of kidney conditions in children.

-

Transcription

Melanie Cole (Host): Robotic Surgery has increasingly become a minimally invasive option for adults in recent years, but what about for children? My guest is Dr. Sean Corbett. He’s a fellowship-trained pediatric urologist whose specialties include caring for a wide range of kidney conditions in children at UVA Children’s Hospital. Welcome to the show, Dr. Corbett. Tell us a little bit about robotic surgery, and what are some of the goals of using it?

Dr. Sean Corbett (Guest): Well, thanks Melanie, and thanks for this opportunity. Robotic surgery is one of the tools in our tool box which has expanded our ability to treat patients of all ages in a minimally invasive approach. The robot just facilitates what we used to or traditionally did with laparoscopic surgery, where it allows much greater range of movement and hand visibility with 10 times magnification, improved precision, high-definition 3D visualization. So it really facilitated our ability to do a lot of things that we’ve traditionally done laparoscopically but now are able to do robotically in a much easier fashion.

Melanie: Dr. Corbett, give us an example of some of the conditions that you’re using robotic surgery to treat.

Dr. Corbett: Sure. Well, there are number of conditions. And really, the envelope continues to be pushed by centers, with the greatest amount of experience here at UVA. Some of the conditions that we’ve treated are certainly most commonly what’s known as hydronephrosis or children with ureteropelvic junction obstruction. We’ve treated them with robotic-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty but also kidney reflux, duplicated kidney systems, ureteroceles, bladder surgery where we need to augment the bladder in the case of children with spina bifida. So really, a whole host of procedures across the board with regards to pediatric urologic condition.

Melanie: Now, what children might this be an option for? Are there some that really are not candidates for robotic surgery?

Dr. Corbett: I think that’s a very good question, Melanie. I think in the appropriate hand, the robot really facilitates robotic surgery across the board. Certainly, in my experience, for the really small child or infants, rather -- and we’re talking less than 5 kilograms, it becomes certainly a much greater challenge to perform a procedure on that smaller, infant, child laparoscopically or robotically. But aside from the size -- and there aren’t a lot of children that aren’t good candidates for robotic surgery unless they’ve had multiple previous abdominal surgeries. That might be the only other indication where robotic surgery is not the best first option.

Melanie: So, Dr. Corbett, let’s talk a little bit about some specific conditions. Hernia repair. This is quite common in children—boys, especially. Tell us a little bit about what’s involved in hernia repair. How would a parent spot a hernia in their child?

Dr. Corbett: Well, a hernia in a small child or an infant, it’s a very different disease condition that it might be in an adult. A hernia in a child is something that’s known as congenital abnormality, and the connection between the abdominal cavity and the scrotum remains open, which allows either fluid to communicate or even the intestines to herniate through. And that is a surgical condition that typically or certainly, traditionally, has been treated with an open incision in the groin in order to repair the defect. But more frequently, we are approaching this from a minimally invasive standpoint and a laparoscopic approach or a laparoscopic percutaneous approach is what I commonly employ in the infants that I’ve worked with. The robot, because the procedure is so quick and have a specific role as of yet in the treatment of this condition.

Melanie: What can parents expect after a hernia? Is there a long recovery period, or are the children pretty much great afterward?

Dr. Corbett: You know, it’s somewhat dependent on the age of the child. But most of the infants and children are back to their normal routine, really, within a day or two. That’s the great thing about the minimally invasive approach, especially, but also working with children infants, is that they tend to recover very quickly and even more so with the minimally invasive approach.

Melanie: Now, so with the robotic surgery, discuss one of the treatments that you use it directly for on children and what you’ve seen as the outcome.

Dr. Corbett: Sure. I mean the most common to these conditions that I would treat with the use of the robot is what’s called performing a pyeloplasty. So we do a robotic-assisted laparoscopic approach, and essentially, that’s a condition where the urine draining from the kidney is blocked at the junction between the kidney, essentially, and what’s called the ureter tube, which is the draining tube from the kidney. So there’s a congenital abnormality that results in a blockage there. So, with the robot, were able to go in, cut out that defect or the abnormal portion, so that you could portion this back together. The children do really well with this. The procedure itself takes about two hours, a little bit longer just in terms of the time that they’ve been in the operating room that’s until to put them to sleep to wake them up, to do the imaging studies at the beginning of the procedure. But the overall procedure is about two hours. The children usually stayed just overnight in the hospital and so, almost all of them will go home by the next morning, or certainly, early afternoon. And they recover very quickly. I mean it’s fantastic to see the difference between the way children recover. When I started this and we were doing all of these procedures through open flank incision—so, a generous incision through the flank underneath the ribcage—and now we do it with three smaller little incisions. So the children do fantastic with it and the repair rates are fantastic. I mean, they’re certainly comparable, if not better, I think in certain hands, then the traditional open or even the laparoscopic approach is.

Melanie: Dr. Corbett, you’re dealing with parents—worried, scared parents. What do you tell them when you say, “We’re going to use robotic surgery.” how do you calm their fears?

Dr. Corbett: Well, I mean I think that’s not significantly different irrespective of the type of procedure that’s being performed. Again, the robotic approach is a minimally invasive approach, just like the laparoscopic approach is, but the goals of the operation are the same, irrespective of how we’re approaching it, whether it’s a minimally invasive or if it’s an open procedure, a traditional open procedure. So, in talking to the parents, number one, I always try to put myself in their shoes and relate it to my own children, and certainly, if they needed this type of procedure, would I have it done on them. Obviously, I think not every child needs an operation, and we’re not going to push it if it’s not necessary. But in those children that are candidates, it’s reassuring to the parents to know that if it was my child, I would use the same technology. Again, we have the capability here at UVA to do it minimally invasively—that’s robotically or pure laparoscopically—or open. But again, I think the benefits of the robot are starting to prove themselves. And again, if it was my child, I would operate on them robotically or have it done robotically, I shouldn’t say. Personally, I think it’s a little hard to operate on your own children, but I think that helps relieve some of the fears or tensions they have to know that we’re doing the same operation irrespective of the approach. But the robot certainly offers a nice approach for them with the same outcomes as the other approaches.

Melanie: Dr. Corbett, in just the last minute, why should families come to UVA Children’s Hospital for their pediatric urologic care?

Dr. Corbett: Well, I think we’re fortunate here because we have some of the greatest specialists certainly in the state. We’re the only institution in the state that offers robotic surgery for pediatric urologic conditions, and so, the expertise that we’ve been able to develop here, I think, is a very nice option for families that want to first do a minimally invasive approach for management of disease conditions within their children.

Melanie: Well, thank you so very much. You’re listening to UVA Health Systems Radio. For more information, you can go to uvahealth.com. This is Melanie Cole. Thanks so much for listening. - Hosts Melanie Cole, MS

Additional Info

- Segment Number 1

- Audio File virginia_health/1429vh5a.mp3

- Doctors Read, Paul

- Featured Speaker Dr. Paul Read

-

Guest Bio

Dr. Paul Read is a board-certified radiation oncologist who specializes in working to develop more effective cancer treatments with fewer side effects.

-

Transcription

Melanie Cole (Host): A team at the UVA Cancer Center streamlining treatments for patients with tumors that have spread to the bone from weeks to a single day. My guest is Dr. Paul Read. He’s a board certified radiation oncologist at the UVA Cancer Center who specializes in working to develop more effective cancer treatments with fewer side effects. Welcome to the show, Dr. Read. Tell us, describe for us how your team’s approach is different for treating cancer that had spread to the bone.

Dr. Paul Read (Guest): All right. We recognize that this is a very painful condition for patients and that anything that we could do make this process simpler for them and more efficient would be of great value to the patient, and their families, who have to bring patients, sometimes from a long distances, to get treatment. We analyze the entire workflow of treating somebody who has spread of cancer to the bone and came up with a strategy that included making sure that all of the people who need to perform a specific task knew exactly when we’re going to treat them, when they needed to do their part, their role. Instead of doing a kind of one day then the next day, then the next day, we were going to do it over very short time period, and also developed whole new systems for doing quality assurance for patients to make sure that the treatments are safe. And when we combined these approaches, we came up with a strategy to treat patients in actually less than a single day. We’re actually looking at patients in under three hours. So they come in and have a consultation with the radiation oncologist, and they have a CT scan. And then we draw on that CT scan the area where the tumor is and what we want to treat, and then we develop a treatment plan and we do the quality assurance, and then we give the patient the treatment, all within about three hours. In most places in the country, when patients go to get treated for spread of cancer to the bone, it’s over a five to ten treatment course. So you can imagine driving back and forth if you live 50 miles from UVA with painful bone cancer, how much better and more efficient this would be for patients.

Melanie: Dr. Read, that’s amazing. Tell us how that multidisciplinary approach, how do you get everybody on the team together for that one day? Aren’t people running in all different directions and busy with different other things? How do you get them all together for that one patient?

Dr. Read: Well, I think the people who are involved include the physicians. People call dosimetrists; who do the radiation planning, CT technologists; physicists, who check the safety of the plan; and then radiation therapist, who actually deliver the treatment. And in addition, the nurse will see the patient to make sure that they have adequate pain management during this process. Redesigning workflows isn’t that hard. All this work has to be done regardless, as long as we basically have built a system where we have email that get sent out to everybody and we also discuss things, that we have a patient that’s coming in two days and this is how it’s -- when we’re going to do this, start the treatment, and this is when the process we anticipate ending it, and we just make sure that everyone knows to adjust their schedule accordingly so that they can do their part. It’d be like if you went to a restaurant for dinner, and all you got the first day was salad, and then you went to the second day and you got your main course, and then you went your third day and you got your dessert. That’s how it currently is in many places. But if you can coordinate it so that you go once and have the entire process, it’s just much easier for patients.

Melanie: I think it’s amazing for patients. So which patients may benefit from this treatment option?